I worked in Canada’s far North for six years in the 1980s, first as a teacher in a fly-in village in Cree territory, then as a teacher and curriculum developer in Algonquin territory in northern Quebec.

During this time, the First Nations were slowly and surely taking back control of their education systems from the federal, and in some instances, provincial governments.

It was a period of intense transition. Aboriginal teachers had to be trained, schools had to be designed in a way that suited the special northern situation, and perhaps most importantly of all, curriculum had to be developed that reflected the children who were the recipients of these new and locally controlled education systems.

One of the frustrating things about this era was the lack of textbooks that reflected the communities in which the schools existed. Kids are kids, no doubt about that, but it seemed that the available books we had to choose from were filled with non-aboriginal stories and images of children doing things that children do in the South.

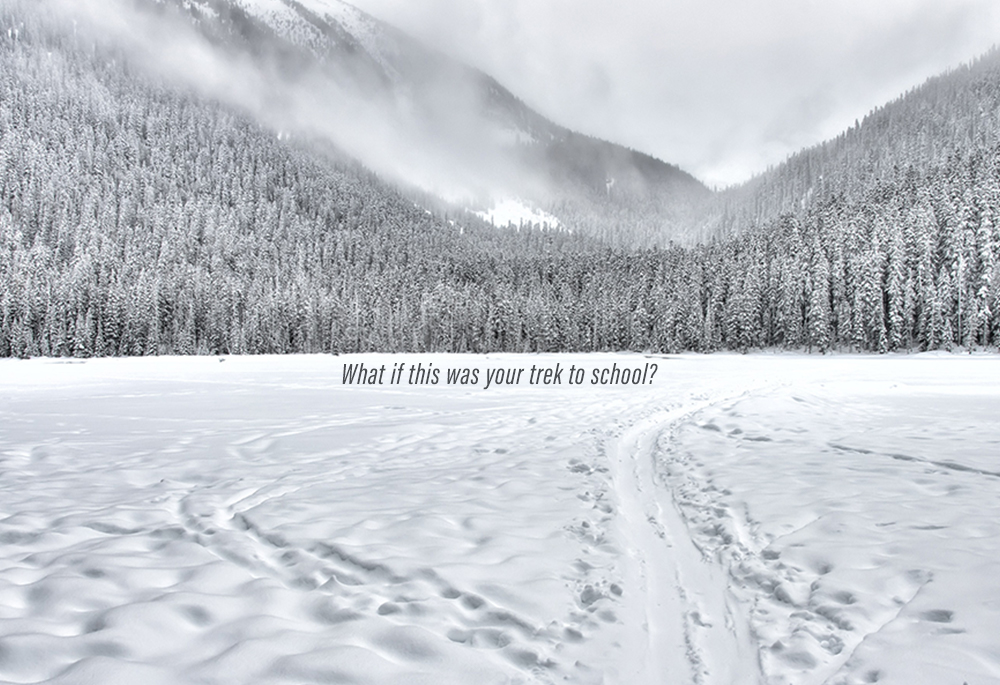

What about the kids whose lives are above the Arctic Circle, or in a land where the temperature drops to minus 30 in November and stays there steadily for the next five months?

Where were the images of children taking snowmobiles to school as their school bus? How could we find stories about kids on traplines and bush camps with their parents and grandparents? What was it like to rise in the winter darkness and get all bundled up for school? What did it feel like to come to the end of the school day and make the cold trek home in the same darkness? Do polar bears really hang out close to schools, and if so, are they perceived as a danger?

We interviewed elders, engaged the entire community and in those pre-computer days, put together simple books, magazines, stories, and images using what now seems like such a primitive process of real cut and paste with an Exacto knife and glue. We brought elders into the classrooms to tell their stories to the eager groups of wide-eyed kids listening at their feet.

Things have slowly changed in the intervening 40 years. Technology has simplified everything. Attitudes are evolving and real control is in the hands of the local communities. There are now many opportunities for teachers and educators to find materials, books, and supports for education in the North, especially among aboriginal people themselves.

Do a Google search with the search parameters ‘books for northern Canada schools’ and hundreds of pages come up. Some are excellent, others simply mediocre, but each of them has something to tell us and to show us about the North. A few of them give us a rare and real glimpse into school life through the eyes of kids in schools up there in the vast northland.

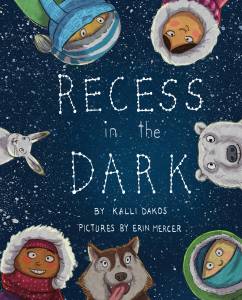

Recess in the Dark is DC Canada’s first contribution to this growing body of work. It tells some compelling stories in poems. And best of all, it is written by a great poet who also spent some great times in schools in the North.

The lovely and realistic poems in this book give us a rich child-eye point of view glimpse into some of the things kids do and think about during recess in the North, throughout the long dark days of winter. The vivid, magical visual images combine well with the rich verbal ones within each poem.

Recess in the Dark is worth a look if you are searching for good materials to convey the spirit of the North to any audience, young and old.